INTERVIEW with Le Mans legend Jacky Ickx

Interviews | crankandpiston | EVO Middle East

For 23 years, Jacky Ickx was the most successful driver ever at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, winning six times between 1969 and 1982, and four times for Porsche. You’d think he’d want to brag about that. You’d be wrong…

Originally posted – 28 June, 2014 | crankandpiston.com

I’ve been privileged during my time with crankandpiston.com to meet and speak with some of the biggest names in motorsport, and the framework for these fascinating conversations is usually the same: an insight into how said name got into motorsport; his or her reflections across a career; set and/or unfulfilled goals; and a snappy quote to wrap everything up. Jacky Ickx though is different.

Here is a gentleman after all with more than 100 Formula 1 starts to his name and is one of only two Belgians to ever win an F1 Grand Prix. He has more than 50 major victories across a two decade-long endurance racing career, and is a six-time 24 Hours of Le Mans winner, a record he held for 23 years until it was overhauled by a plucky Dane called Tom Kristensen in 2005.

The old rose-tinted glasses, I had assumed, would be working overtime during our chat. Apparently not…

“If you offer a driver one win at Le Mans, he will not take it with one hand, he will grab it with two hands! So you can imagine winning six times is very special,” Jacky explains. “But I’ve always said that records, whatever they are, are there to be beaten. At some point and with a bit of luck, Tom Kristensen will win Le Mans for a 10th time. And that’s absolutely incredible! That’s a record that will never be beaten.”

Within seconds, focus has bounced from Jacky to his record-holding successor, and I’m a little thrown. I mean… between 1967 and 1983 after all (discounting DNFs), his lowest finish at Le Mans… was 2nd. And in the late ‘60s, he even competed in a staggering 84-hour endurance race around Europe’s most notorious circuit – the Nürburgring – with only one co-driver. Twice!

If anybody has earned the right to talk about his achievements, it’s Jacky Ickx.

But no. Nursing an espresso – and encouraging me to try one, since they are ‘rather good’ – this amiable gentleman prefers to focus more on his contemporaries, both in and out of the driver’s seat, than his own record.

“There is something relatively unfair in motor racing,” he continues. “You only see under the spotlight, that is the drivers and the winners. But you have to show your admiration for all these engineers, all these talented people, especially because Le Mans has changed a lot since 1998.

“It is not an endurance race anymore. We use the term to say it’s long distance, but it’s not ‘endurance.’ It’s a Grand Prix. It’s flat-out for the engineers, mechanics and drivers, and that is spectacular. Already we’ve seen an outstanding, action-filled race, full of incidents and brilliant driving. What we are watching is the pinnacle of motor racing, and we should all be grateful for the opportunity.”

It’s this ‘pinnacle of motor racing’ in which Jacky took six victories (four of which were with Porsche) between 1969 and 1982. Strange to think then, despite growing up around father Jacques’ career as a motorsport journalist, that motor racing never interested a young Jacky…

“I actually wanted to become a gardener when I was 16! I was taken to races and found them very boring: I used to say, ‘please don’t bring me there again’. Maybe it comes from the fact that I was very poor at school and couldn’t pay much attention. My parents were frustrated, but began rewarding me when my grades started improving. The more successful I was, the bigger gift I got at the end of the year. One year I received a bike [a 50cc Puch] and with that, I discovered the pleasure of being on the podium. For me that was new and exciting.”

Suddenly the enthusiasm that was lacking during Jacky’s first visit to a Grand Prix in 1955 started to grow with each competition. Class championships soon came his way, opening the door to four-wheel competition.

“I was doing well in motorcycle racing and someone asked me if I’d like to drive a car. It was a BMW 700 coupé with the boxer engine from a motorcycle, and that was the first real production car from BMW in 1963. I drove that and drove it well. Then someone came and said ‘would you like to drive a Cortina?’ Then it was a Ford Mustang. By then I was attracting attention from Ken Tyrrell [the F1 team principal that led Sir Jackie Stewart to all three of his world championships.]

“Soon I was driving a Formula 3 single seater, and by 1967, I was in Formula 1. So it all happened quite quickly. But it was all down to timing. And destiny.”

Leaning heavily on his bike racing experience, F3’s newboy quickly established himself as a phenomenon in the wet (“you have to be very gentle with the throttle, otherwise you’re on the floor, and that hurts!”). In one of his first F3 outings in 1966, Jacky decimated the field at a sodden Silverstone to finish 3rd, ahead of some of F1’s most respected names and despite starting from the back.

After a period with Matra and Cooper, a Ferrari contract was in Jacky’s pocket for 1968, his first victory coming just six races later at Rouens. Had circumstances been different, the ’68 crown might well have been his, but a leg-breaking accident in Canada with just three races to go brought his challenge to a premature end.

Gentlemanly conduct during the 1970 season meant Jacky finished runner-up – as he had done the year before with Brabham – to F1’s only posthumous world champion, Jochen Rindt. It would be the closest the Belgian came to taking the crown, and though his F1 career continued intermittently for another nine years, Jacky stood atop the podium only twice more.

F1’s loss was sportscars gain, however. While it was close but no cigar on the F1 scene in 1969 for example, the first of Jacky’s Le Mans victories came with the Ford GT40 that year in – what remains to this day – the closest-ever finish at Le Mans. Barely three car-lengths separated Jacky’s GT40 from Hans Hermann’s 2nd-placed Porsche 908 after 24 hours of racing.

“Ah yes, Hans Hermann is a lovely, lovely man.” – Jacky’s first espresso is now long-gone, and another is en-route. – “I rarely speak to him about this era because he was beaten by 120 metres, so that was obviously very frustrating. But, when you are 23 years old, as I was then, and you have to fight against a person who is 34/35, as Hans was then, things are different. When you are young, you have no fear. You brake 10 metres later. If your opponent goes 100kph into a corner, you go 101kph!

“When you’re 40 there is no way you can drive like someone who is 20. You become wiser and you don’t take the same risks.”

It’s a telling comment from Jacky, given that his win in ‘69 was not the only talking point that year.

Since its inauguration in 1923, the ‘Le Mans start’ – whereby drivers sprinted across the track and clambered into their idling cars – had been an event staple. But as a demonstration against motor racing’s ever-increasing risks, in 1969, Jacky calmly walked across the track to the Ford instead, taking the time to buckle his race harness before driving off.

It was a unanimously unpopular move, but a prophetic one. On lap one, John Woolfe’s Porsche 917 speared into the barriers, an incident he would have survived had his seatbelt been buckled properly. By 1970, the traditional Le Mans start was gone.

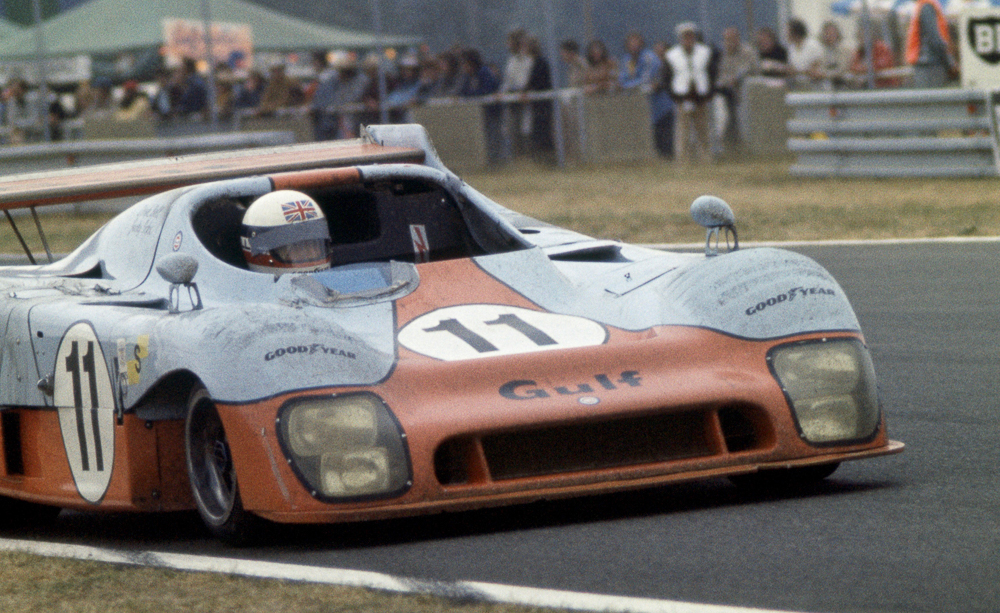

In 1976, one year on from his second win (and his only one aboard a Mirage), Jacky began an eventual 10-year tenure with Porsche. A fruitful relationship it proved too, netting the Belgian four further Le Mans wins. Once again though, Jacky is unwilling to hog the credit for these achievements.

“My future in Formula 1 looked uncertain, and in the early days I was doing a lot of long distance racing. So for me it seemed a great opportunity to say yes to Porsche’s offer to join them and their new product in 1976.

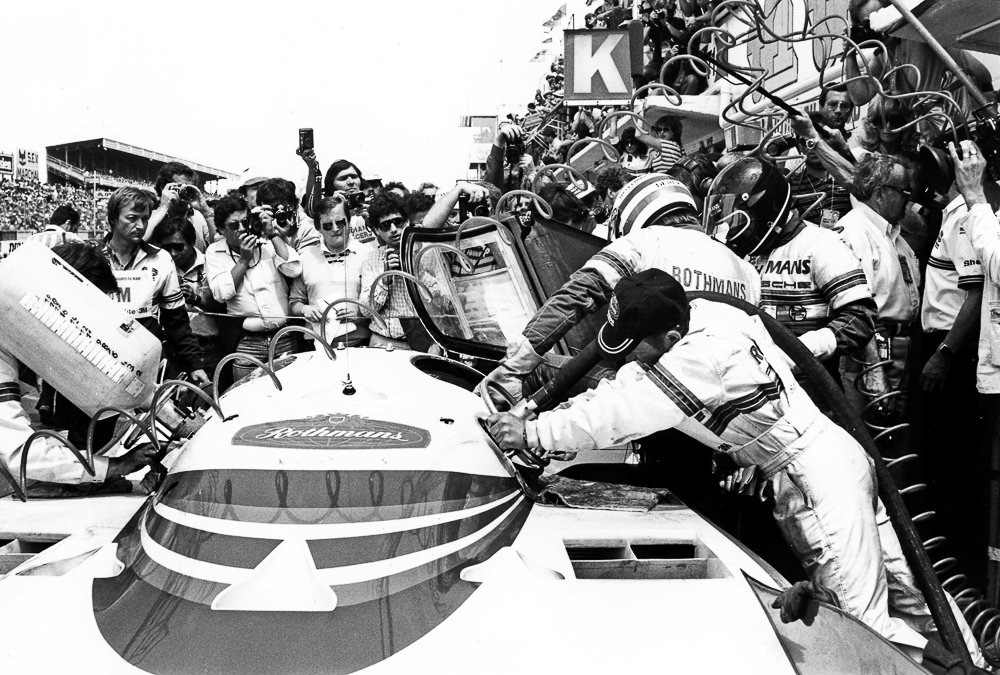

“If you drive for Porsche, your chances of winning are greater. I won two times when I was almost a kid, and won four times with Porsche. But what you have to keep in mind is that I raced for 10 years with Porsche, and 10 years in the same team is a hell of a long time. Normally you don’t stay with the same team too long. So when I think about it, they are the reason of my success in long distance.”

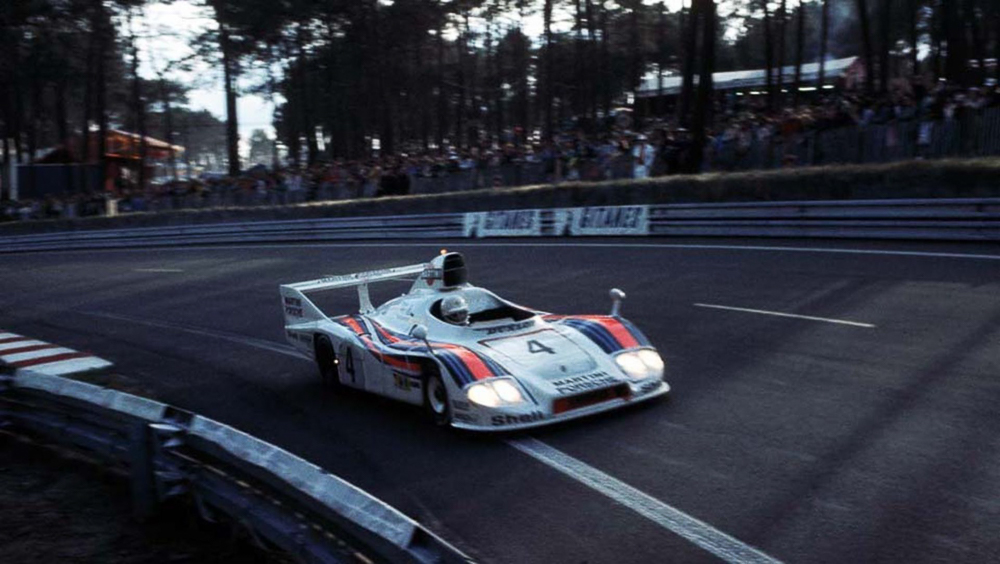

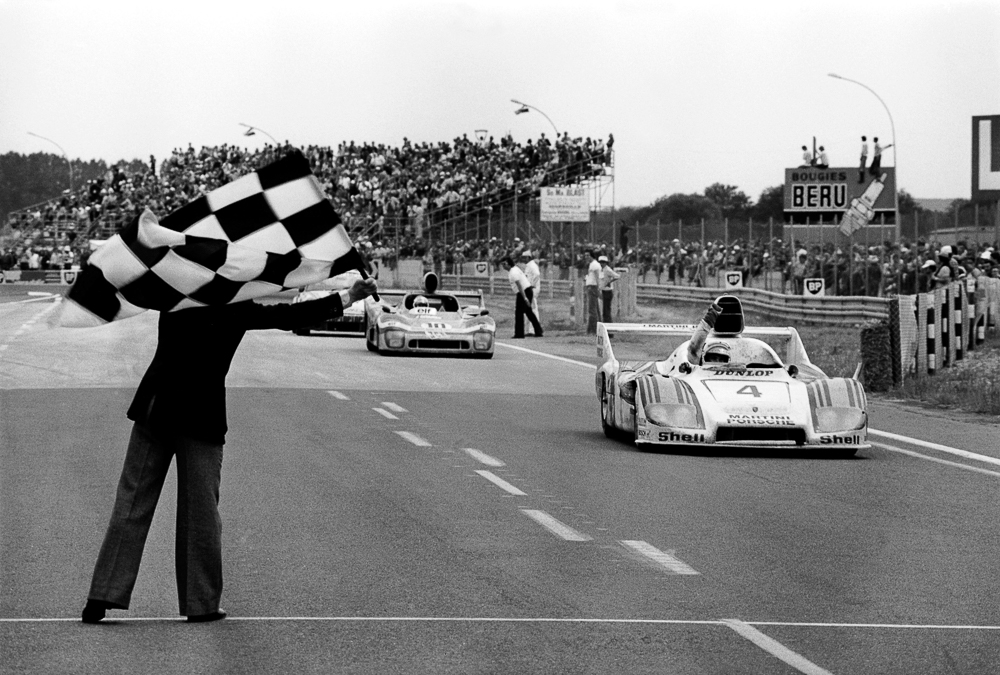

Though his final victory in ’82 was secured with Porsche’s vaunted 956, Jacky’s true cash cow was the 936, with which he took three of those six wins in ’76, ’77 and ’81. His ’77 win in particular was the result of sheer grit and determination, as an engine problem just four hours into the race dropped Jacky, Hurley Haywood and Jürgen Barth to dead-last at one point.

It’s as I nurse my own espresso – he’s right, it really is rather good! – that I ask whether the 936 holds a special place in his heart…

“The car you prefer is always the winning one!” he laughs. “When you win, no one complains about the car, and I drove in many different races so I have a lot to choose from!

“The car is basically the same: four wheels; a manual gearshift; no brake assistance; no steering assistance; no automatic gearbox; no cooling system. I come from the motorcycle world, and I learnt the difficulty of road racing in my early days. So that helped a lot when I started racing cars. But I was not good at everything. In rallying for example, I was very bad. So, you know I’m far from perfect.”

This ‘far from perfect’ rally record of which he speaks includes an overall win on the fearsome Paris-Dakar Rally in 1983, just FYI. Not that Jacky mentions this of course. Nor indeed his return to the event – aged 55 – in 2000 alongside his daughter Vanina. Focus instead shifts to Porsche’s first tentative steps onto the Dakar sands in 1984…

“The Dakar was strictly reserved for Toyota, Land Rovers, Mercedes, etc. And when we – Porsche – came in, everybody said we had no chance. But we won the first in 1984, lost the second in 1985, and won the third in 1986.

“The third one we won with a flat-six, twin-turbo engine, and electronic axles, and we put that in the middle of the desert. The whole team for three cars was 18 people for a gruelling event across 12,000km of desert. But we knew it could be done. That’s all about Porsche.”

By 1985, his F1 career long done and with his 41st birthday looming, Jacky Ickx finally hung up his helmet when a collision at that year’s 1000km of Spa (not of Jacky’s doing it must be said) cost German sensation Stefan Bellof his life. Fittingly, Jacky would sign off his professional racing career with victory at the Malaysia 800km that December.

Though modesty (apparently) forbids Jacky Ickx from thinking too wistfully about his own long-distance achievements, you’d be wrong to mistake this for indifference. Even if he prefers to leave the rose-tinted spectacles in their case most of the time, the passion for his race clearly still burns very deeply, nearly 30 years on.

“Racing is not just about speed. What these boys are doing is a Grand Prix for 24 hours. They have to give it 100 per cent at all times. They have an engineer who tells them to switch this button or that button every 20 seconds. They have to visualize the quantity of energy they have, the fuel they have. It’s so complicated. And then they have traffic to navigate around. It’s an enormous challenge. So congratulations to them. All of them.

“Yes, I have reached 390kph down the Mulsanne straight here, but this is not fascinating. When you have done it 10 times, you say ‘give me an extra fifty horsepower’, pass 400kph, ask for more, and so on. The excitement for me comes from the fact that you belong to one of the best, and – if possible – are the best. The true excitement comes from winning. I am not that romantic!”

Images | James Gent, Porsche AG and Historic Motorsport International

Interviews | crankandpiston | EVO Middle East | James Gent