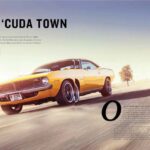

DRIVEN. 1970 Plymouth Barracuda

Feature | crankandpiston.com / EVO Middle East

As the pony car wars reached their height in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Ford Mustang reigned supreme. To many though, the Plymouth Barracuda left its own mark on history.

Originally posted – 11 May, 2015

crankandpiston.com | EVO Middle East magazine (PDF)

One of the perks of life at evo Middle East is the access this brings to some of the automotive world’s more stunning – and often historic – machines. In the last few years for instance I’ve taken a monster truck for a spin in Abu Dhabi, driven a Ferrari at full(ish) lick around Fiorano, and even wangled a go in another privately-owned classic American muscle car: you may remember the ’79 Trans-Am we featured a couple of months ago. And yet despite all this, as I slide into the driver’s seat of this Plymouth Barracuda, I’ve got some serious butterflies.

For starters, since this particular model rolled off the production belt in 1970, it has had only three owners, each of whom was fastidious about maintenance. Save the re-dyed front seat, everything is of original spec and has been imported from America. On the day of our shoot, I’m even shown a white folder containing every receipt, service document and warranty slip it’s accumulated. It has racked up 259,000 kilometres – or from Dubai to its original home in Houston, Texas, around 20 times – without any major issue. Alongside its $52K(ish) market value today, almost $15,000 has been spent on import and restoration charges alone. One of only three generations of Barracuda produced between ‘64 and ‘74, it’s arguably one of the rarest pony cars currently in the Middle East.

If all that wasn’t enough, current owner – and all-round top bloke – Nader Elkhodary has promised the Barracuda to his daughter Salma when she’s old enough to drive.

She’s three years old.

And today, I’ve been entrusted to take this meticulously kept future birthday present for a spin. Gulp.

On top of all this, Nader, who I suspect is secretly enjoying my ever-heightening nerves, casually mentions that there are some power steering issues he hasn’t managed to get sorted yet, for which he apologises.

To me. The ham-fisted oaf who’s about to take his beloved classic car for a drive.

I get the feeling Nader and I are going to get on well today!

Truth be told, the third gen example you see above, though completely stock, is a far cry from the original Barracuda that arrived in 1964, a mere two weeks before its principal rival – the Ford Mustang – made its debut.

Based on Plymouth’s already established ‘Valiant’ for example, the first-generation Barracuda even featured the same engine line-up as its compact saloon sibling. And inevitably, Plymouth’s insistence on marketing the Barracuda’s ‘convenience’ and ‘practicality’ over its sportiness saw the Mustang outsell its principal rival almost eightfold in the first year alone!

Slightly larger engine options were made available for 1965 (output from the 273cu in V8 was upped to 235bhp), it would be another two years before Plymouth started taking ‘the pony car wars’ seriously.

Though still based on the compact Valiant’s platform (it would be another three years before the commonality between the two was ditched), mercifully the brand-new second gen Barracuda was bigger, more aggressively designed, and featured a more daring engine line-up, and was thus more effectively positioned to take on the newly launched Chevrolet Camaro and Pontiac Firebird.

Ironically, this just sparked further problems.

So hefty was the Barracuda’s new 383 cu in V8 for instance, squeezing a power steering pump into the diminutive engine bay was not physically possible, resulting in less-than-brilliant handling (leaving no room for air-conditioning didn’t help much either). To avoid direct comparisons with its sister Belvedere model, power was cut from 325bhp to 280bhp, much to the chagrin of potential customers.

Still, the redesign had struck a chord with American audiences, and while the Mustang continued to heavily outsell its competition, Barracuda production in 1967 rose by more than 50 per cent over the previous year. Now fully committed to producing a high-performance pony car, Plymouth went for broke in 1970 with a completely redesigned third generation. And finally got it right.

Larger, lower, wider and more aggressively designed than ever, the ’70 model shared much – including a platform – with its recently debuted sister model, the all-new Dodge Challenger. Bigger than any of its predecessors, almost every engine on Plymouth’s line-up was made available for the third gen Barracuda. Plymouth was so committed to the muscle car arms race in fact that a ‘Cuda – the name confusingly given to the 335bhp V8-powered top-drawer equivalent to the Barracuda – even contested the prestigious Trans-Am Series in 1970, driven by no less a man than Dan Gurney! For the first time in six years, Plymouth had finally found a Barracuda that could compete on both a visual and performance level with the segment’s biggest contenders.

Ironically, as customer interest in pony cars started dwindling, rejuvenated sales figures proved too little too late for the Barracuda, and just four years later in 1974, Plymouth’s pony car was no more.

“Everyone goes for a classic Mustang or Challenger, but you just don’t see a Barracuda on the streets anymore,” Nader explains as we circle today’s test model. “Day-by-day it’s disappearing from the market. And that’s what interested me about the Barracuda. I wanted something different.”

Inadvertent parallels with Bumble Bee aside, I fast see Nader’s point as I deposit myself in the leather driving seat. Though my eyes are drawn to the retro collection of dials and switches on the dash – as well as the authentic Texas number plate sitting on the rear parcel shelf – directly in front of me is a magnificently slender and elegant rim blow wooden steering wheel. It’s beautiful to behold and almost impossibly delicate to the touch.

And, unfortunately, solidly fixed in position. With barely an inch between the wood-grain and the top of my thighs. I attempt to remedy this rather awkward driving position by sliding my seat back as far as I can on the runners, only to discover that Nader has already done so. Even though our drive this afternoon isn’t particularly long or laborious, I’ll effectively have to drive bow-legged, taking care as I do so not to ride the brakes, given the incredibly close proximity of the pedals.

In another direct hit to my ever-raising blood pressure, Nader reminds me that if the engine should stall – “it does that when the AC is maxxed” – I should press the red button on the dash beneath the speedometer and keep the revs high. “Oh, but try not to go overboard as this can cause some problems with the carburettors.” Right…

A turn of the key and the V8 is fired into life. Sort of. The opening ‘tirade’ is unlikely to open the gates to eternal damnation, but I can’t help but smile as revs sent through the right pedal cause the enormous 5.2-litre unit to bank slightly in the engine bay: you can even feel the resonation flowing through the cabin.

The butterflies are flapping furiously as I slip the three-speed automatic into drive, give all 318 cubic inches a poke, flick the almost-impossibly thin indicator stalk down, and pull out into traffic.

And straight into a problem.

In order to counter the air-conditioning’s stranglehold over the engine, Nader recommends I shift into neutral when stationary to keep the revs up. Advice I immediately forget when, braking for the first junction, an object flying off the parcel shelf and over my left shoulder alarms me to such an extent, that for a split second I think the rear window has collapsed. As it turns out, it’s the period-savvy Texas number plate that has fallen into the rear footwell. It’s enough to rattle me significantly though, and as I slow to a halt at the junction, I forget to shift into neutral.

The engine stalls. And it’s only after a few hair-raising seconds that the big V8 turns over and we’re on the move again.

My dignity damaged beyond repair, I’m now I’m REALLY nervous. We’re barely 200 yards in and I’ve already given Nader sufficient reason to pull the plug on our drive. An option which, sportsman that he is, he decides against.

Kick from 230bhp through the rear wheels as I enter the highway is not as aggressive as I’d expected. Both the mechanical bluster and the accompanying road noise hit new heights of fury, but the pull itself is surprisingly linear. Almost gentle. At a brisk 97kph (in my still slightly rattled state, I’m having difficulty working out the conversion on the US-spec speedometer) and with seemingly no more surprises in store, I start very gradually to relax.

Which, despite the fact my legs are straddling the steering wheel, proves quite easy. There’s buckets of head and legroom: were my arms and legs just a couple of inches longer, I could probably drive from the rear seats. Were I to do that of course, seeing the rev-counter down by the gearlever – an aftermarket mod – would be quite difficult. I’d also be unable to make use of the airplane-like seatbelt that’s currently wrapped around my waist (there is a shoulder strap but Nader assures me this isn’t necessary).

What is slightly concerning me though is the steering. It’s incredibly light, with barely any connection to the front wheels registering at all. This detachment is compounded yet when, having hit a dip in the road, the softened suspension causes the nose to pull slightly – though no less alarmingly – to the right. To make matters even worse, traffic has started to slow, and within minutes the Barracuda’s rev counter is dropping perilously close to the 1,000rpm mark.

If I stall the Plymouth here, there’s no fall-back. No plan B. Only several hundred irate commuters venting their collective wrath in my direction.

Fortunately rear visibility over both shoulders is so good, I can weave from lane-to-lane without crawling to a stop, although the biblical amounts of bodyroll that this produces means it’s not all plain sailing.

And yet despite all this, despite the pressure of keeping the revs high, the wheels straight, and myself from sliding through the window if I take a corner too quickly, I’m enjoying my drive in the Barracuda. Seriously enjoying it.

There’s such an enormous sense of occasion from behind the wheel, the sound of ‘70s Americana emanating from under that long, rippled bonnet going hand-in-hand with the iPhone snaps passers-by and my fellow motorists are aiming in my direction.

Unlike other performance-focused cars I’ve driven in the past, there isn’t the pressure to ‘push to the limit’ in the Barracuda either: the ‘cruise’ is mesmerizing and, frankly, hard enough work as it is. And while that may seem like I’m taking an ungrateful swipe at this beautifully restored classic, it’s a sensation that Nader himself shares. Very rarely does he max that big V8 since, to him, the cruise IS the experience, and I really see what he means.

I’ll admit my time with the ‘70 Barracuda has been at times hair-raising, almost constantly stressful, and leaves me with a dull ache in my left knee that stays with me for a few days afterwards. But quite honestly, I’ve loved it.

It’s been an experience, the one-of-a-kind type I was hoping for from a 1970s pony car. I wanted a reminder of a period in automotive history long since gone but always revered. A time when power, looks and straight-line grunt were preferable to manoeuvrability, Ferrari-esque levels of handling, and easy Bluetooth connectivity. I wanted to be reminded why, almost half a century later, car fans the world over still yearn for a piece of the muscle car era, or in this instance, the pony car wars.

Clearly I’m not alone, as three meticulous owners of this magnificent machine have so eloquently demonstrated.

Images | Awesome Group and Arun M. Nair

Feature | crankandpiston.com / EVO Middle East | James Gent