A brief history of the Sebring International Raceway

Feature | CREVENTIC

In 2021, the 24H SERIES made his first visit to the Sebring International Raceway. At the time, the Hankook 24H SEBRING was the latest chapter in a 70-year history…

Originally posted – 13 November, 2021

CREVENTIC (PDF)

“A win here lasts forever”

It’s one of the lesser-known quotes attributed to Dan Gurney, and followed an historic first international sports car win for Toyota, orchestrated by the former Grand Prix winner’s own All-American Racers. Fittingly, the ’92 (and, latterly, ’93) triumph were just the latest Gurney celebrated at Sebring. Indeed, having also won the 12 Hours as a driver in 1959, the ’67 Le Mans winner was a charter member of the Sebring International Raceway Hall of Fame, and, in 1996, became an intrinsic part of the circuit’s history when ‘Big Bend’ was renamed in his honour.

Many would doubtless agree with Gurney: a win at Sebring is like few others, steeped as they are with seven decades of heritage.

Construction of, what would later become, the International Raceway began in June 1941 on land donated by the city of Sebring. Granted, racing was still almost a full decade away and the site, replete with runways and barracks, actually started life – briefly – as an airbase.

By the turn of 1942 however, plans were in place to extend the base into a Combat Crew Training School. The runways were fortified accordingly to withstand the might of B-17 and B-24 bombers. The base would later be renamed Hendricks Field in honour of First Lieutenant Laird Woodruff Hendricks Jr, a native Floridian who tragically died in 1941 during a training exercise in the UK.

Come the end of global hostilities, the genesis of the Raceway emerged in 1949, when Sam Collier and Bob Gegen – keen sports car racers, both – spotted the airfield while flying overhead. The pair quickly sought out air terminal chief Allen Altvader and, indirectly, the Sebring city council for permission to host a motor race on the runways of the (now) civilian airport. Tragically, Collier would never see his plan come to fruition as, just a few months later, he was killed in an accident at Watkins Glen.

Enter Alec Ulmann, former president of the Dowty Equipment Corporation that manufactured landing gear for military aircraft, and another gentleman racer keen to see European-style ‘Le Mans’ racing interpreted in the United States. Back, once again, Altvader went to Sebring’s committee, who, buoyed by Ulmann’s enthusiasm, plus the money he himself would use to finance the inaugural event, gave it the greenlight.

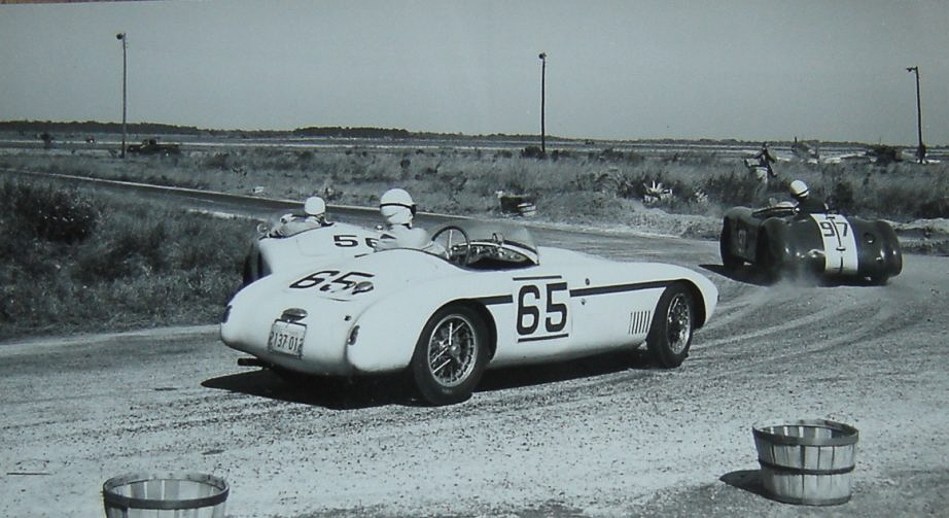

Not that Sebring’s first-ever motor race held a candle to the ‘12 hour’ behemoth it would later become. In fact, by contrast, the event was borderline primitive.

Strategically placed haybales marked out both the 5.632km / 3.5-mile course and spectator stands. This turned out to be particularly helpful for the competitors, few of whom had any idea where they were going on the airbase’s sprawling interior roads. Even Ulmann broke protocol, of sorts, when he took then governor of Florida Fuller Warren for a hot lap of the new ‘circuit,’ while the race was on-going!

That the winning entry – Fritz Koster and Ralph Deshon’s Crosley HotShot – had been borrowed from a spectator shortly before the race got underway was chaotically apt.

Nevertheless, the Sam Collier Memorial Six Hours, held on New Year’s Day in 1950, raised sufficient interest to warrant a second edition in 1952. One that would instead take place in March, and with an altogether more ambitious 12-hour format.

Gone too was the ramshackle 1950 course, replaced with a longer 8.368km / 5.2-mile layout that utilised the former army base’s roads as well as the North/South and East/West runways. Notably, the concrete originally laid in 1941 remained intact, as indeed it does to this day.

One year on from the inaugural Sebring 12 Hours (won, incidentally by Harry Gray and Larry Kulok), a team entered by Briggs Cunningham – most famous for his America’s Cup victory in 1958 – took the first of three consecutive wins with, quite remarkably, three different car makers and six different drivers. One of whom, in 1954, was a certain Stirling Moss.

Further cementing their names in the record books, Cunningham, and drivers Phil Walters and John Fitch also became the inaugural winners of the first-ever round of the FIA World Sports Car Championship in 1953. Just as Tom Kristensen, Rinaldo Capello and Allan McNish would win the inaugural round of the FIA World Endurance Championship – also held at Sebring – 59 years later.

Few achievements in Sebring’s early years were as momentous though as Ulmann’s coup in 1959 when Formula 1 arrived in Florida. Ironically, what should have been an easy-draw for Sebring proved to be anything but.

Questionable marshalling was an on-going concern. Six reserve drivers ran laps at the 1955 Sebring 12 Hours, and an un-registered Fiat 500 managed to complete the Grand Prix’s National Compact car support race in 1959 without the officials even noticing! On top of that, the combination of a multi-textured surface and fragile single seaters with ‘50s-era reliability meant that, by the end of lap 24, more than half of the grid had already retired, including championship contender Stirling Moss. With a commanding 1-2 for Cooper seemingly in the bag, much of the assembled crowd had already started heading home as the ’59 United States Grand Prix entered its closing stages.

Prematurely, as it turns out. With just one mile to go, leader Jack Brabham suddenly ran out of fuel on the final lap, and with his first World Championship at stake, ‘Black Jack’ was forced to push his recalcitrant Cooper across the line. Brabham’s ill-fortune thus left the way clear for teammate Bruce McLaren to take his first F1 victory, becoming the youngest ever winner of a Grand Prix in the process. A record the McLaren founder would hold for an incredible 44 years, and was only bested when Fernando Alonso emerged victorious at the 2003 Hungarian Grand Prix.

Even late-race drama though could not grip the Sebring crowds. In the face of disappointing ticket sales, Formula 1 ventured Riverside-wards for 1960 before finding its US home for the next two decades at Watkins Glen. As far as F1 goes, Sebring was one and done.

A lost Grand Prix would be the least of the Raceway’s concerns though as the 1960s rolled by. Ferrari’s dominance of the 12 Hours – the Scuderia won seven out of nine editions between 1956 and 1964 – seemed to be coming to an end, and ahead of the 1966 12-hour race, a podium sweep at that year’s Daytona 24 Hours suggested the new Ford GT40’s reign was just about to begin. Indeed, Shelby’s first win at Sebring with Ken Miles and Lloyd Ruby was the first of three in four years for the Blue Oval (ironically, the ’66 win had looked set to go to Dan Gurney only for his GT40 to run out of fuel on the last lap).

Sadly, the ’66 race very nearly spelt the end of Sebring’s motorsport heritage altogether.

A passenger after his rear brakes seized, Canada’s Bob McLean tragically perished when his GT40 hit a telegraph pole at the end of the Hairpin (remnants of the Mk.1 Ford are still buried at the site). Several hours later, Mario Andretti’s gearbox-less Ferrari 365P2 was clipped by Don Wester entering the Webster Turn, and though the American survived his trip into the spectator area with only minor injuries, wreckage from his Porsche 906 ended up costing five people their lives.

Sebring’s reputation was in tatters, lawsuits were threatened, and plans were quickly put in place to move the ‘Sebring’ 12 Hours to Palm Beach for 1967. Circuit owner Pete McMahon even pledged $1.5 million in track upgrades to get the ‘Florida International Grand Prix of Endurance’ off the ground. Only unprecedented amounts of rainfall prevented construction – and thus a 10-year deal – from being completed, and the Sebring 12 Hours, begrudgingly, remained in-place for 1967. Albeit with significant track modifications.

The Green Park Chicane’s introduction in place of the old Webster corner remained the most significant track change until 1983, when the north face of the circuit was moved away from the runway, and the Backstretch was relocated to a perimeter road to make room for new paddock facilities. In a fitting tribute to its earliest benefactor, who would pass away just two years later, the new Backstretch was renamed the Ulmann Straight in 1984.

Ironically, having come so close to the brink in 1966, Sebring’s biggest event was cancelled altogether in 1974 when skyrocketing oil prices led to fuel shortages. Plans to keep the 12-hour race alive as a 1,200km event or reschedule to October came to naught, and the Raceway went silent in March for only the second time since 1950. Not that it stopped fans turning up in support anyway though…

In 1987, the revised turn one-to-three complex was rerouted from the runways altogether, the first steps to establishing the Sebring International Raceway as a permanent facility. Indeed, by 1991, further revisions significantly reduced the old Warehouse Straight, and just like that, the 5.954km / 3.7-mile Grand Prix layout synonymous with Sebring today was born.

Further history was made in 1999, when, under the directive of new owner Don Panoz, further investment was injected into the circuit’s paddock and pits, and its neighbouring facilities. The FIA’s return in 2019 led to a second pitlane being constructed along the Ulmann Straight, and an epochal era of international sports car racing at Sebring was soon underway. Just as Porsche’s Carrera RSR, 935 and 962 had obliterated its competition between 1973 and 1988 (BMW’s win in 1975 is the sole outlier), Audi Sport would rewrite the history books anew across the 2000s with its diesel and hybrid R8s.

In 2021, CREVENTIC adds its name to an illustrious list with the first, 24-hour international motor race to be held at the former Hendricks Field. It’s a daunting challenge for both organiser and competitors, down not only to the concrete-asphalt surface on which they will race, but the seven decades of history on which it lays.

A win here last forever, after all.

Images | Petr Frýba, Sebring International Raceway, and Porsche

Feature | CREVENTIC | James Gent